It’s been one year since the racial uprisings of 2020 swept the United States and inspired millions of people around the world to reflect on the pervasiveness of systemic racism in society. This civil rights movement also led our North American Jewish community to begin engaging in collective, critical dialogue about bias, white supremacy, and the ways in which people of color have been systemically excluded and harmed within our community. These conversations resulted in numerous organizations undergoing internal audits, investing in diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) trainings, and releasing statements of solidarity. Additionally, many organizations came to the realization that if they truly sought to be inclusive, representation mattered and more room needed to be made for Jews of Color to step into leadership. While this awareness has led many organizations to diversify - or commit to diversifying - their teams and boards, it is imperative that organizations remain Jewishly reflexive in this process to avoid succumbing to performative, symbolic diversification efforts that result in tokenism, rather than increased representation.

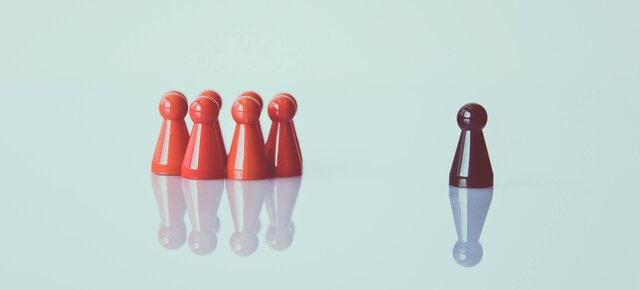

While both are connected to diversity efforts, tokenism and representation are drastically different and it is important to understand the distinction. Tokenism results when institutions make performative efforts towards the inclusion of people from underrepresented groups to give the appearance of equity. Token leaders are typically few in numbers and are often unfairly asked to speak on behalf of their entire community. Their ability to stand up to oppressive ideas also becomes diminished by their fear of being punished or speaking out with no support. Similarly, if they do speak out, sheer exhaustion of being the only person to ever challenge normative thinking eventually leads them to become suppressed, apathetic and serve only as symbols of a failed diversity effort. In contrast, representation takes place when organizations apply an equity lens, and involve a wide range of people with distinct backgrounds to bring new perspectives and reimagine the processes.

To better understand the dangers of tokenism, let’s take a look at Jewish history. During the 19th and 20th centuries, when antisemitism in Eastern Europe lead to violent pogroms throughout the region, a small number of Jews tokenized as “good” and “well integrated” were left unbothered and used as examples for what Jews desiring to live in the Russian Empire “should look and act like.” In this case, tokenism left “good” Jews feeling conflicted and powerless and gave the oppressors a reason to justify the pogroms as not anti-Jewish, but rather anti- “good cultural fits” for the Empire. This pattern of moral licensing is a well-documented phenomenon that continues to take place today.

If an organization’s diversity efforts mean solely hiring and promoting folks who essentially share and advance the same perspective, not only is that structure closing itself off to change, it’s tokenizing people who they know will never challenge the status quo. An antidote to this behavior takes place when hiring teams challenge their own thinking and move forward with hiring or promoting a set of diverse candidates who demonstrate a desire or foresight to “challenge the way things have always been done.” To complement this shift we must also reflect on personal and institutional bias that has resulted in us passing over or rejecting certain candidates, and letting go and replacing past team members. Like all reflexive processes, the point is not to undermine people of color who have been hired or promoted, but to help identify biases that are likely still present and keep us blindly protecting and upholding systems of oppression. In short, representation is not only a diversity framework, it’s a model for belonging that is rooted in Jewish values.

Taking time to contemplate the role that Judaism can play when carrying out diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) initiatives, is a vital piece to the sustainability of this work. At a quick glance, it is simple to see how tokenism limits our ability to live out the values of b'tzelem Elohim (in God's image) and kavod (respect), which teach us that each person has a unique light worth honoring, celebrating and treating with respect. On the other hand, when reflecting on representation, one can see that these two values are not only upheld, they are also complemented by our Jewish commitments to kehillah (community) and tzedakah (justice). Incorporating a values screen to our work is a reflexive practice that roots our commitment to DEI with kavannah (intention.) These values can also guide us in prioritizing interventions that center human dignity rather than advancing quick-fixes that can cause greater harm to our community.

As our Jewish community continues to embark on efforts that advance racial equity and justice, it is important that we proceed with intention and that we hold ourselves and our organizations accountable when missteps happen. For organizations working on diversifying their teams and boards, ask yourselves: What needs to shift within our organization to ensure that new leaders are set up for success? How can we ensure this does not become a situation of tokenism, and rather an opportunity for empowered representation? How can we do this work Jewishly? And although good intentions are present, how will our team and board tend to impact when harm happens?

The road to equity is not straightforward. It’s long and it requires commitment, flexibility, stamina, and humility. Performative activism is easy, nurturing belonging with a values-based, Jewish mindset is the real task at hand.

Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash.

Get To Know The Author

WFF Dr. Analucía Lopezrevoredo (Class 5) is the Senior Director for Project Shamash, a racial equity and leadership development initiative from Bend the Arc and is also the Founder and Executive Director of Jewtina y Co., a Jewish and Latino/x organization on a mission to nurture Latin-Jewish community, leadership and resiliency, and celebrate Latin-Jewish heritage and multiculturalism.