When I was a young rabbinical student around 1993, I visited the childhood home of a woman I was dating. She was from a strong and proud Jewish family, and her parents were intrigued that their daughter was dating a future rabbi. It was not your typical “meet the parents” scene. Her mother did not want to know what my plans were for their daughter; she wanted to know what I thought the future held for American Jewry!

Caught off guard, and not sure that as a 24-year-old graduate student I was in a position to opine authoritatively about the Jewish future, I tossed out the first coherent thought I could generate: “I think the Jewish community of the future will be smaller and also more intensely Jewish.”

I believe that prediction is on its way to coming true. There are many factors that influence the size, scope, makeup, and overall health of our Jewish community. But the economics of Jewish life undoubtedly constitute a significant part of it. The relatively small, intensely-committed core of the Jewish community has gotten stronger and more deeply committed, and that core is willing to expend ever-greater resources on accessing Jewish life. The rest of the Jewish community experiences cost as yet another barrier to Jewish life (on a long and growing list).

The way we use our financial resources is one of the clearest reflections of our values. When the Torah talks about money, most often it is in the context of our obligations to others: to God, the kohanim (priests), the community, and those in need. When America talks about money, most often it is in the context of the accumulation of personal wealth or the acquisition of material possessions. So American Jewish life is caught in the tension between these two fundamental approaches to economic life.

Most of the Jews who came to America brought with them a strong commitment to tzedakah. But they also arrived penniless and seeking economic opportunity. Our community prioritized education, social welfare, caring for the sick, poor, elderly, and religious needs. The marketplace promised nearly limitless opportunity for personal enrichment.

For most of the 20th century, the tension between the value of tzedakah and the value of accumulating wealth was largely resolved by the steep upward trend of prosperity among American Jews. An ever-increasing number of immigrant families and their children and grandchildren were able to fulfill their dreams of wealth while still easily affording and providing for a robust Jewish life. In the post-war years, there were countless single-income families who could pay for Jewish and secular education, synagogue dues, summer camp, Federation contributions, and more, without sacrificing the nice house in the suburbs, family vacations, and other material luxuries.

But Toto, we’re not in 1950 anymore. I would contend that a “perfect storm” of factors has cause a shift in the economics of Jewish life in the 21st century. A sampling of those factors:

- The costs of providing services and programs have risen faster than incomes.

- Real wages for middle and working class Americans have been stagnant for a generation; the gap between wealthy and poor has grown significantly.

- Shrinking membership/enrollment in Jewish organizations means the fixed costs are not divided among as many households.

- The cost of college education has outpaced growth dramatically.

- Jewish communal infrastructure is overbuilt, both in terms of organizations and buildings, and the aging and/or declining among them are slow to adapt or fold.

Given all of this, the calculus for those of us charged with exercising leadership in the Jewish community has changed drastically. We have to work this challenge from both ends: the economic and the educational.

We must be bold and creative in reducing economic barriers to Jewish life, using every means at our disposal: philanthropy for scholarships, collaboration to share costs, re-allocating resources to fund the most promising and attractive programs, merging or sunsetting inefficient or duplicative organizations, adjusting our real estate footprint, and more. We need to bring the cost closer to the place where it meets the capacity and will of the Jews who are seeking access to Jewish life.

But we also have to work the educational angle, helping Jews understand why Jewish life in all its forms is such an important force in the world and in their lives. If we grow the number of Jews who see the ennobling and profound benefit of living a life committed to the Jewish mission in the world, their financial priorities will shift to the benefit of the whole community.

Our tradition’s values are timeless. Even though they may be countercultural in some of the places we live, those values constitute a compelling way of life. Jews have always valued earning a living, even a comfortable one; but we have valued caring for our community and those in need even more highly. As we model our own commitment to sustaining that which has always been precious and sacred to our ancestors, may we embody a vision of Jewish life that every Jew can, and will, buy into.

Get To Know The Author

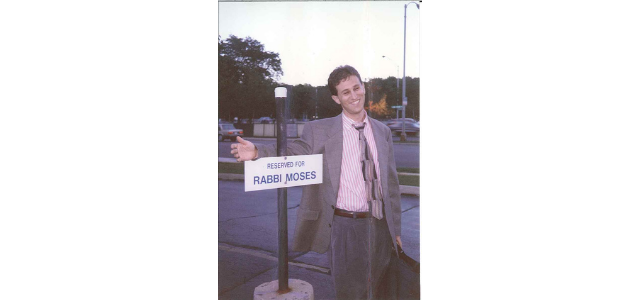

WGF/DS Alum Rabbi Jay Henry Moses (Class 5) is a Vice President of The Wexner Foundation.