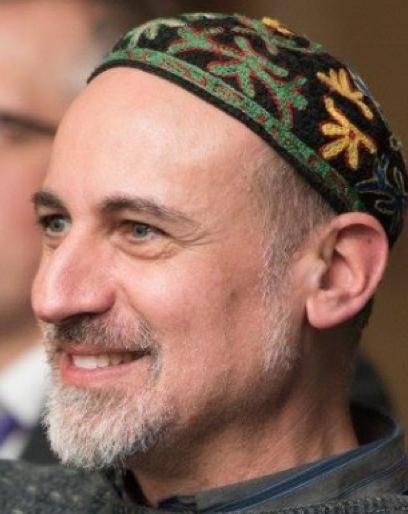

A comfortable, well-educated, straight White male rabbi walks into a multiracial family. That’s not a joke - it’s my spiritual autobiography.

Though every story is unique, “comfortable” does describe many of us who grew up White and Jewish. We rarely knew how advantaged we were, in myriad subtle ways, how much likelier we were to achieve success, thanks to something as random as skin tone and how hard others would find the same journey. Like most, I was blind to the extent of White privilege. Seeing is painful, but it’s necessary. Barukh pokeach ivrim – blessed is the One who opens unseeing eyes.

My beloved kids (aged 15 and 11), who are of color, have experienced blessedly few overt acts of racism – yet. They have faced shining micro-aggressions and had some scary interactions; a level of ever-present fear is part of our family’s operating system. While my wife’s and my racial consciousness developed partly from this particular parenting journey, it’s grown more from something that’s equally available to those in monochromatic families: solidarity. The effort of opening one’s eyes begins with seeking out perspective and information that we miss, by design, in a racist society.

White folks may doubt the extent of White privilege until we learn how pervasive the disenfranchisement of people of color has been across a literally white-washed history. Our blind spots remain huge until we develop and deepen more friendships across difference. We may think little of well-meaning congregants peppering the tallit-draped siddur-following Black or Latinx person with questions, or the armed guard at the synagogue entrance whose limited anti-bias training can’t undo a lifetime of racial tropes, until we learn the lived experiences of countless Jews of color (yes, including rabbis’ children).

Let’s hear stories, bear witness to challenges, experience the fullness of everyone’s humanity, over and over. This is our call as humans and as people of faith and conscience, especially now: Encounter. Read. See. Listen. Learn. Grow in awareness. Stand up for racial justice.

To state the obvious, the murder of an already-handcuffed George Floyd under the knee of a White officer of the law, though horrific, was barely an outlier. It was brazen; in broader daylight with more onlookers and cameras nearby than most. It opened many eyes to racism’s pervasiveness. But eyes will blink, then they tend to wander, and eventually eyelids close. Will White America (or Israel, or Canada,) return to its ostensibly colorblind, deeply unjust, thoroughly-suffused-with-racism slumber? Will we let it?

Today’s hope comes from such a wide swath of society finally joining communities of color in feeling troubled. Whoever enjoys light-skinned advantage must remain “willing to tolerate the discomfort associated with an honest appraisal of our internalized superiority and racial privilege,” (per Robin DiAngelo, author of White Fragility). Exactly why I opened with the idea of being comfortable. The journey of opening eyes is “an ongoing and often painful process of seeking to uncover our socialization at its very roots. It asks us to rebuild [our] identity in new and often uncomfortable ways.”

Today’s hope comes from such a wide swath of society finally joining communities of color in feeling troubled. Whoever enjoys light-skinned advantage must remain “willing to tolerate the discomfort associated with an honest appraisal of our internalized superiority and racial privilege,” (per Robin DiAngelo, author of White Fragility). Exactly why I opened with the idea of being comfortable. The journey of opening eyes is “an ongoing and often painful process of seeking to uncover our socialization at its very roots. It asks us to rebuild [our] identity in new and often uncomfortable ways.”

Religion exists “to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.” Abraham Joshua Heschel is often credited with this maxim; actually, it was Chicago satirist Peter Finley Dunne describing journalism. But it’s true and profound and entirely consonant with the prophetic mandate to which Heschel and our tradition call us. Heschel did warn of the pervasive “coalition of callousness” that blocked social consciousness. Before a June 1963 White House meeting on race, he telegrammed, “DEMAND OF RELIGIOUS LEADERS PERSONAL INVOLVEMENT NOT JUST SOLEMN DECLARATION.” He marched in Selma – and we’d best spend more time marching ourselves, avoiding what he called “the evil of indifference,” than we do just telling his decades-old story.

Inasmuch as we’re comfortable, we must be willing to afflict ourselves – to open our eyes to the injustices of the world; to see through the artificial social construct of “race,” and to understand how operative a category “race” remains. And to the afflicted, including Jews of color and others in our orbits, we owe comfort – which is to say, solidarity.

An important aside for any light-skinned Jewish reader who squirms at “we White people:” the reality of antisemitism does not negate the fact that most Ashkenazi immigrants’ children could buy homes, benefit from government programs like the GI Bill, enjoy police protection, gain education and enter the upper and middle classes in ways that most Americans of color could not. We must own that reality. Identities are multiple and intersectional. Most Jews enjoy “provisional whiteness,” even as Jews of all races face challenges and dangers of our own. Race and religion loom large, but so do gender (half of us are women) and class (this straight White male grew up in poverty). Among us are disabled, queer, accented and other “otherized” people. We’re all a mix of advantaged and disadvantaged. And “White privilege” is real.

The deadliest example of racial dis/advantage? Covid-19. People of color are likelier to get it because disproportionately they’ve been denied the benefits of equal education and opportunity and are clustered in lower-income professions without the easy option to telecommute that so many of us enjoy. People of color are likelier to require hospitalization and die from it because of inequal health factors – less access to insurance and to quality health care; living in areas with worse air pollution and less healthy food choices; more underlying conditions. The first and worst-hit victims of climate change, likewise, are poor people of color. Racism is deadly. We must open our eyes to it and be actively anti-racist - its elimination must be our priority

To fully open eyes is not easy. We continually ingest racist messages; as Ilana Kaufman (of the Jews of Color Field-Building Initiative) reminds us, racism is in the air we breath and water we drink. It's like spinach salad, in public intellectual DJ Jay Smooth’s brilliant analogy. Generally clean people, who still get gunk in their teeth, need others to point it out. Likewise, fundamentally good people still display racism. Let’s not get defensive when someone calls us on racial insensitivity; we should thank them! There’s no simple surgery to remove racism once and forever, because it’s a continual barrage, requiring continual awareness. Smooth summarizes, “we need to move away from the tonsils paradigm of race discourse, toward the dental hygiene paradigm of race discourse.”

And when we do shift paradigms and commit to racism and white fragility’s ongoing life-long antidote of “sustained engagement, humility, and education,” – these are DiAngelo’s words, which we might call middot, worthy attributes – we will find ourselves on “the most exciting, powerful, intellectually stimulating and emotionally fulfilling journey.”

Let’s demand “personal involvement, not just solemn declaration,” from ourselves as well as others. And let’s keep marching together.

Photo credit: Clay Banks on Unsplash.

Get To Know The Author

WGF Alum Rabbi Fred Scherlinder Dobb (Class 6) serves Adat Shalom Reconstructionist Congregation in Bethesda, MD.

Other posts by this author ›