Antisemitism has been called the world's oldest hatred. It's the shoe that has fit just about every kind of foot on paths of blame, violence and cultural misdirection winding through the world for more than two millennia. It is also the world's easiest hatred.

It’s easy for haters to access a vast pool of myths, images and false notions that fester even underneath the surface of societies where Jews and Judaism feel most at home. The horrific shootings at the Tree of Life Congregation in Pittsburgh make this sad truth ever so easy to see.

After Pittsburgh, as hard as it may be for some of us to believe the sharp increase in antisemitism in recent years, it’s easy to know what to do. By the millions, we mourn the dead, we comfort the wounded and broken, we stand together with fellow Jews and allies, and we tirelessly protect the people, institutions and public and private spaces upon which antisemitism can wreak havoc.

Be they the first responders taking bullets for victims of antisemitism or Wexner alumni taking those first responders chicken soup as they heal, people of good conscience can’t and won’t give an inch to evil.

Sadly, it’s easy to know what to do about antisemitism, because we have had to do something about it for thousands of years. But there is also something else very easy about antisemitism. Something to which Jews — particularly Jewish leaders — must pay attention to even as they fight tooth and nail against it. Namely, for many of us running or supporting organizations, a major portion of our success depends upon raising money. Like it or not, it is precisely the emotions sparked by and driving antisemitism — anger and fear — that make it easiest to pull on hearts and purse strings.

Again in these moments, it’s easy to know what to do. We jump into the abyss created by extremes to serve the community. We leverage these threats into resources. And we use those resources to do good work. But the hard part in these moments of extremes and leverage is not taking our eyes off of the successes in what has arguably been one of the most powerfully effective periods of investment in Jewish meaning, innovation and strength the world has ever known.

In Israel and North America we live in a hard-earned age of renaissance — from social start-ups to Waze, from independent minyanim to powerfully independent Jewish figures in every form of art and culture, from programs training every kind of Jew to lead every kind of community to a language called Hebrew and a country called Israel that were just beginning to find their way into modernity a mere century ago.

Sometimes we need anger and fear to drive our passions to build something new or defend what must be protected. But as we protect our communities, we must also remember the generative work of building communities depends on more than anger and fear. It requires investment in joy, compassion, creativity and diversity.

Our job to disrupt, disparage and destroy antisemitism in all of its forms is paramount, but we are at our best as leaders when we frame our narrative and raise and invest our resources based on values and visions not framed by the haters, but by and for the people and ideas that we love.

Get To Know The Author

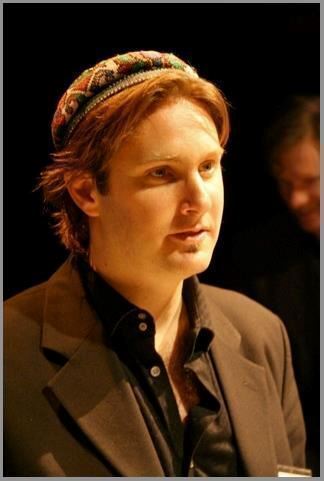

Wexner Graduate Fellow Dr. Stephen Arnoff (Class 13) has served as Executive Director of the Fuchsberg Jerusalem Center of the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism (USCJ) since January 2017, responsible for overseeing all operations and programming at a thriving hub of Jewish study and culture in the heart of Jerusalem, including the Conservative Yeshiva, Nativ, and much more. He has served in senior leadership roles in the Jewish community for much of the past two decades.