Judaism was founded as an alternative to the worship of power.

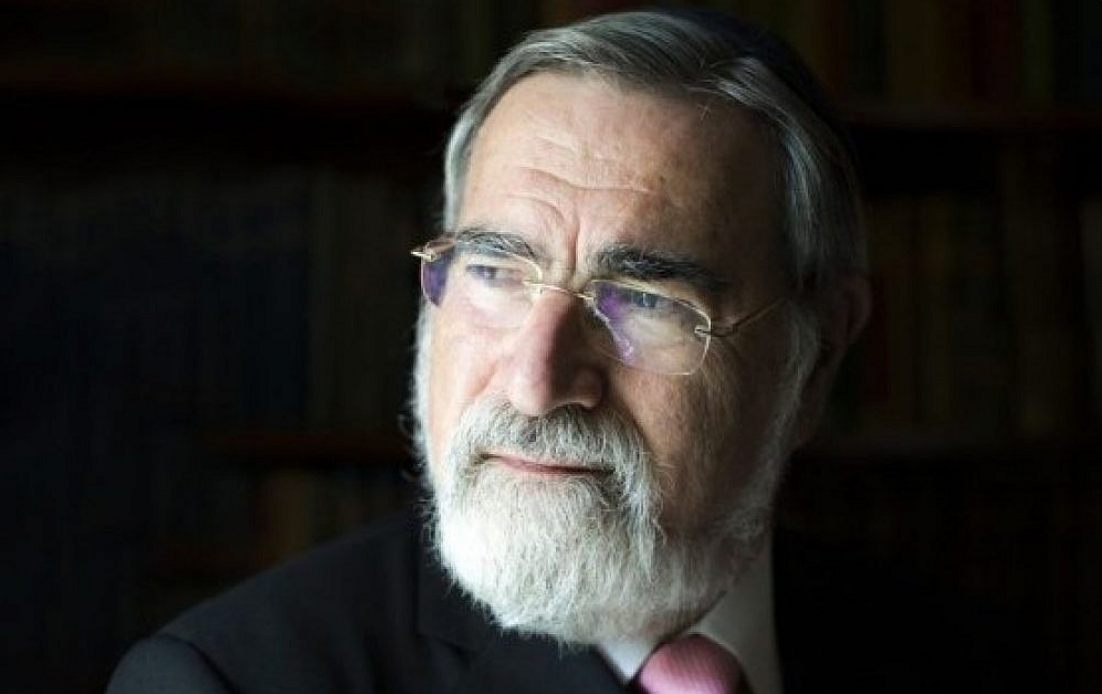

That’s what Chief Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, alav hashalom, taught on Lech Lecha. “I want you, says God to Abraham, to be different. Not for the sake of being different, but for the sake of starting something new: a religion that will not worship power and the symbols of power – for that is what idols really were and are.”

Sacks continued, “Judaism is a sustained critique of power. That is the conclusion I have reached after a lifetime of studying our sacred texts.”

Look at what we do worship instead: malchut. Every prayer we utter is to Melech ha’Olam, a Power positioned above and often at odds with human power. It’s as if the Rabbis were saying to the pharaohs of their day, “There is only one true King and it isn’t you.” Marc Tzvi Brettler teaches that in the ancient Near East a king was also a judge and a shepherd, and this mixed metaphor made its way into our conception of God. Our King became a Judge more fair than any judge, a Shepherd more caring than any shepherd.

Psalm 72 asserts that a human king should be like Melech Ha’Olam, dedicated to mishpat v’tzedek. Rabbi Dr. Andrea Weiss teaches that the terms mishpat and tzedek, when paired, refer to justice and righteousness specifically in regard to the poor and oppressed. The psalm says, “May [the human king, emulating God] bring justice to the lowly of the people… rescue the children of the destitute and crush the oppressor.” In other words, when we call God Melech, we are holding up a model of power that prioritizes justice for the marginalized and caring for the vulnerable.

Judaism, therefore, is not opposed to power as long as it is applied to right ends, with mercy for those who need it most. Perhaps the best articulation of this is the Gevurot prayer: “You are forever powerful, God. You give life to the dead, You sustain life through lovingkindness, reviving the dead with great compassion, supporting the fallen, healing the sick, freeing the captive, keeping faith with those who sleep in the dust.” The Power we worship acts with lovingkindness and is dedicated to those who have no power themselves: the fallen, the sick, the captive and even those who sleep in the dust.

As we mourn Rabbi Sacks in a nation that prides itself on liberty, in the aftermath of an election where the abuse of power was very much on the ballot, it is timely to reflect on the persistent allure of the worship of power in light of Judaism’s long rejection of that very thing.

Get To Know The Author

WGF/DS Alum Rabbi Rachel Timoner (Class 17) is the senior rabbi of Congregation Beth Elohim in Brooklyn.