11

Jun 2019

When Yitro came to Pittsburgh

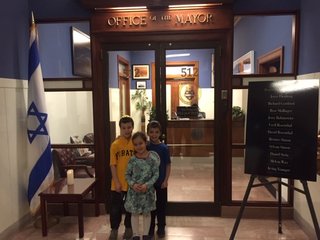

The author and his family hosted the actress Mayim Bialik when she visited Pittsburgh earlier this year.

“.....Set these over them as chiefs of thousands, hundreds, fifties, and tens.” Exodus 18:21

Picture the scene: The Jews are about to receive the Torah at Mount Sinai. After having endured much hardship, Moses finally reunites with his wife, children and father-in-law Yitro (Jethro). He captivates them with the story of God rescuing the Israelites from the world's greatest superpower, Egypt and how he, Moses, assisted in leading millions from prolonged slavery to unbounded freedom. Yet in what should have been a euphoric atmosphere, Yitro observes something out of place. After successfully leading his people through the largest extended crisis in its history, Moses, while known as the most-humble human being, should still be feeling confident in his abilities. Instead, what Yitro sees is a burnt-out leader who is on the verge of being overwhelmed. He recognizes that while Moses's solo leadership style has had a positive outcome in his first crisis, a collaborative approach must be utilized going forward if Moses is to successfully navigate future challenges. The leadership farm system must be developed. Yitro remedies this by setting up a hierarchical court system involving four levels that treat cases according to their severity. Moses would then be involved in only the most challenging case. Now, instead of one Moses tackling multiple problems, there would be 131 leaders per every thousand Israelites joining in the process (one head of a thousand, ten heads of a hundred, twenty heads of fifty and a hundred head of tens.) By creating this system, Yitro saves Moses's well-being, affords him the opportunity to excel at his expertise and enables other leaders to successfully share in crisis resolution.

Fantastic, you say? Chalk one up for Biblical Leadership. But how does this translate to us today?

After the largest Antisemitic attack in American history, Pittsburgh was in a position that American Judaism had not encountered. Swift action and leadership needed to be taken immediately for a community that needed assistance. But what route should be taken? Should a solo organization take the lead to streamline efficiency? Could many different organizations of various sizes and missions move forward together? Could a crisis leadership blueprint from Biblical times be applied to modern-day practice? Here are some examples of how it did.

After the largest Antisemitic attack in American history, Pittsburgh was in a position that American Judaism had not encountered. Swift action and leadership needed to be taken immediately for a community that needed assistance. But what route should be taken? Should a solo organization take the lead to streamline efficiency? Could many different organizations of various sizes and missions move forward together? Could a crisis leadership blueprint from Biblical times be applied to modern-day practice? Here are some examples of how it did.

"Yitro"

Relationship building outside the tribe. Yitro was a Midianite leader, not an Israelite, although he subsequently converted. While the nation being affected was not his own, Yitro chose to offer his assistance and guidance in the spirit of broader people-hood. So too in Pittsburgh. Although not directly affected, the Muslim, Catholic and Sikh communities (among many others) offered great assistance, both financial and emotional. Our politicians and law enforcement, while technically having an obligation to help, went above and beyond in countless ways to support the community.

"Moses"

The top of the chain. Just like in Yitro's system there were certain things that could not be solved by the community alone. In our case, this could include the monetary help that poured in from all over the world. The mental health trauma specialists that came in for extended periods. The Dream Doctors Project from Israel, a medical clown troupe that flew in for a week to help children and adults process trauma. While communities should always strive to be self-sufficient, there should never be shame in seeking outside assistance when necessary.

“Chiefs of Thousands”

Help from the largest organization. The Jewish Federation of Greater Pittsburgh, the largest and most far-reaching local institution, had the ability to play the part of the "connector" and helped to link people, ideas and resources that wouldn’t normally bump into one another. They took care of the immediate time-sensitive difficult decisions, funded a month of free security to every Jewish institution, made sure collected monies were being done so properly, organized funerals, helped with immediate victim family needs, etc... But they could not do it alone.

“Chief of Hundreds”

“Chief of Hundreds”

The next level down. The Jewish Community Center became the headquarters and second home for law enforcement and families affected by the massacre. The substantial Rabbinic leadership across all denominations who brought comfort to their flock. Jewish Family and Community Services saw to the enormous task of mental health counseling to all those in need, including a joint program with the Federations' Jewish Education and Capacity Building Division that tailored counseling specifically to the aforementioned community Rabbis who tend to take care of others and forget about themselves.

“Chief of the Fifties”

The next in size but no less important. All three Jewish day schools excelled at counseling their students. Hillel on campus made sure every student was reached out to and had a safe place to go. And in what will always be remembered, the Chevra Kadisha spent multiple 24-hour days working with law enforcement to make sure every victim was treated with the utmost respect and adherence to Jewish law.

“Chief of Tens”

The smallest in numbers. The neighbors, family and friends who offered words of encouragement and sympathy. Community members who organized a local 24-7 Shmirah (watching) list at the morgue so that no victim would ever be left alone. Store owners who placed signs of empathy in their windows.

Do I think that Pittsburgh really broke out the Yitro playbook

Do I think that Pittsburgh really broke out the Yitro playbook when it came to managing our crisis? Not really. Yitro's system was made to move away from a system of solo leadership and accordingly create a hierarchical system to treat problems according to the severity of the issues. What his plan did for us was set a precedent for collaborative leadership for future generations. Our community was uniquely positioned in that we already had a cooperative system in place, pre-massacre. The system treated all issues as important and delegated them according to size, expertise and need. Because of this, our community was able to work in near perfect harmony to effectively manage this crisis. Egos were cast aside and bridges were built when necessary. Like in Biblical times, this ensured that leaders were better prepared and people were more effectively served.

when it came to managing our crisis? Not really. Yitro's system was made to move away from a system of solo leadership and accordingly create a hierarchical system to treat problems according to the severity of the issues. What his plan did for us was set a precedent for collaborative leadership for future generations. Our community was uniquely positioned in that we already had a cooperative system in place, pre-massacre. The system treated all issues as important and delegated them according to size, expertise and need. Because of this, our community was able to work in near perfect harmony to effectively manage this crisis. Egos were cast aside and bridges were built when necessary. Like in Biblical times, this ensured that leaders were better prepared and people were more effectively served.

The Midrash teaches us that when God was preparing to give the Torah, all the mountains stepped forward and declared why they thought the Torah should be given on them. "I am the highest mountain," said one. "I am the steepest," said another. One by one, they all asserted their claims. In the end, God chose Mount Sinai not because it was the tallest or the grandest, but because it was the most humble. In terms of Jewish community, Pittsburgh may not be the largest, most wealthy or even have the most Kosher restaurants. What we do have is a community founded on a bedrock of collaboration, humility and bridge building that serve us well both in tranquility and in crisis. The lessons learned at the Mountain (Sinai) continue to be utilized on the Hill (Squirrel).

Get To Know The Author

Wexner Heritage Member David Knoll (Pittsburgh 18) is a born and raised New Yorker, but considers Pittsburgh his true home. After a career as a Bond trader in New York City, David traveled the world for a year as a tour guide for a luxury Kosher travel agency. He then met his beautiful (and vastly more intelligent) wife on his return to NYC. They decided to move South, to Palm Beach, Florida, where he was on the ground floor of an attempt to build a new city on Grand Bahama Island. After the birth of two wonderful boys, and the subsequent Recession, he convinced his wife to move back to her childhood home in Pittsburgh. David and his wife have since had a third child and have never once regretted their move.

Other posts by this author ›